Being at the heart of the world of art, Parisian jewelry designers were desperate to find an innovative design language, and pioneering artists such as Rene Lalique and Henri Vever explored the path of Art Nouveau.

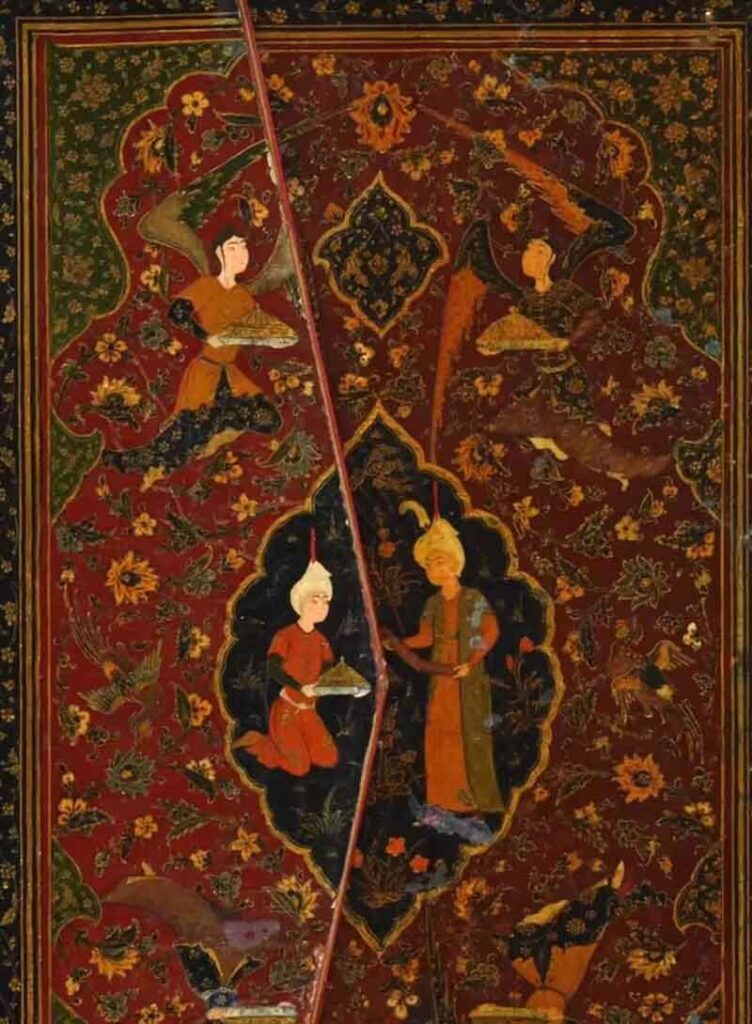

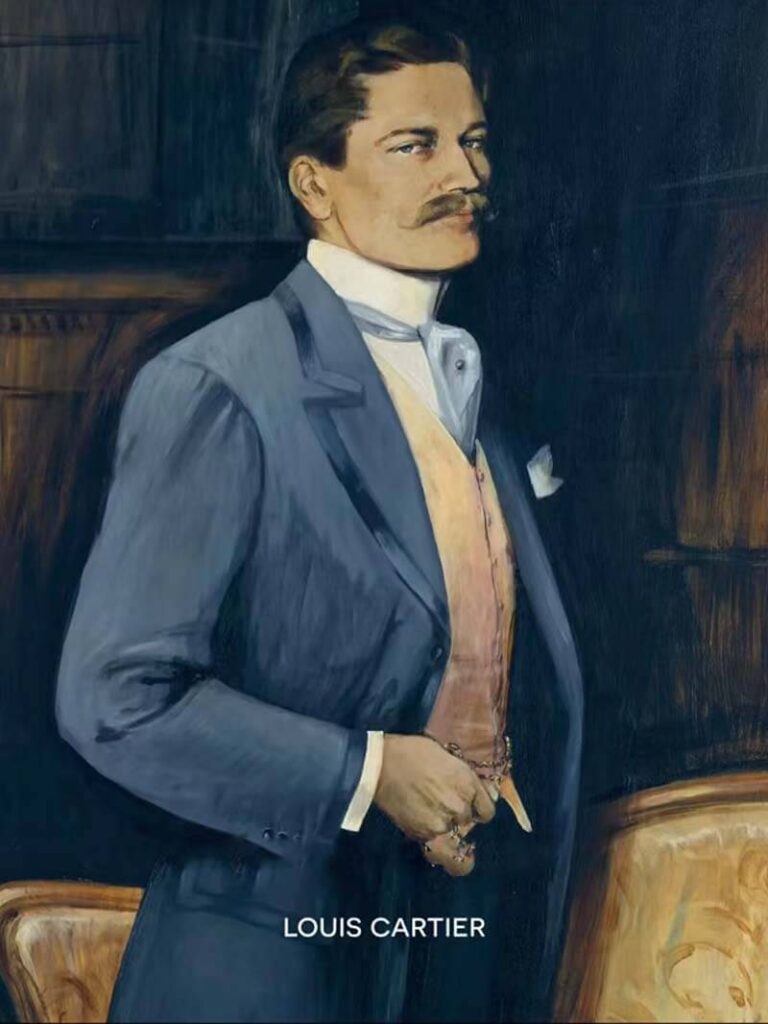

Around 1910, two exhibitions on Islamic art made a huge impact on Louis Cartier. He was impressed by the magical stories, the fine miniatures, the clashing colors, and the geometric patterns.

Louis Cartier, a man of extensive knowledge and taste, was indifferent to this naturalistic, figurative aesthetic. He was looking for an entirely different style. Cartier was a tireless patron of the Parisian art market, where the world’s finest Persian and Indian rare books, miniatures, objects and manuscripts could be found.

He opened his collections and books to the brand’s designers, providing them with a constant stream of novel themes, motifs, and color inspiration for their jewelry designs.

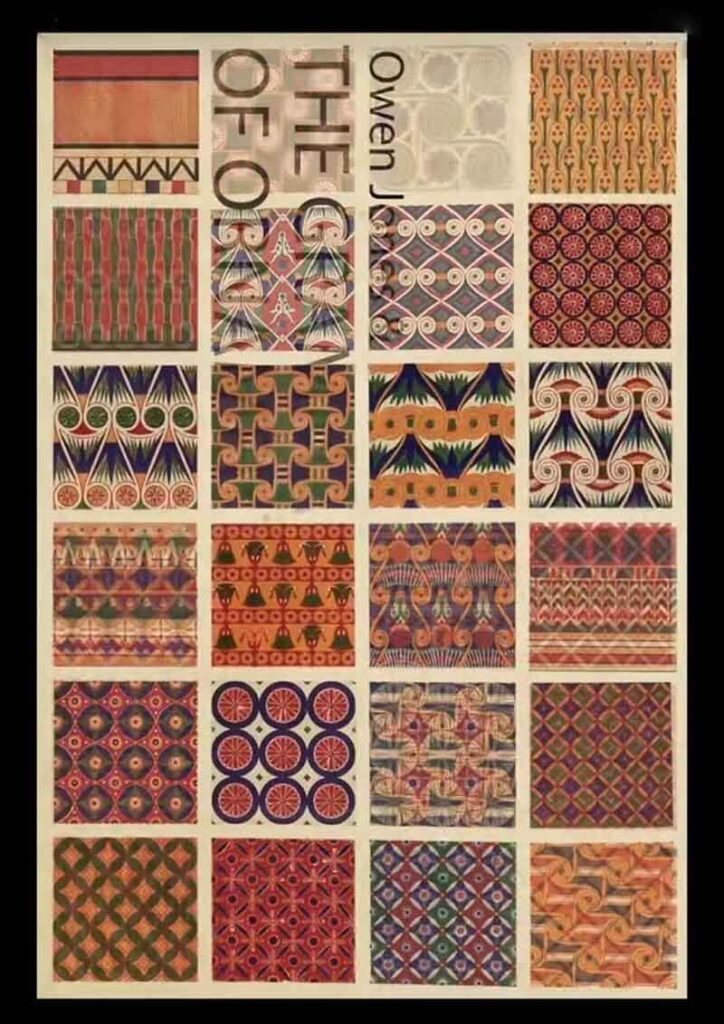

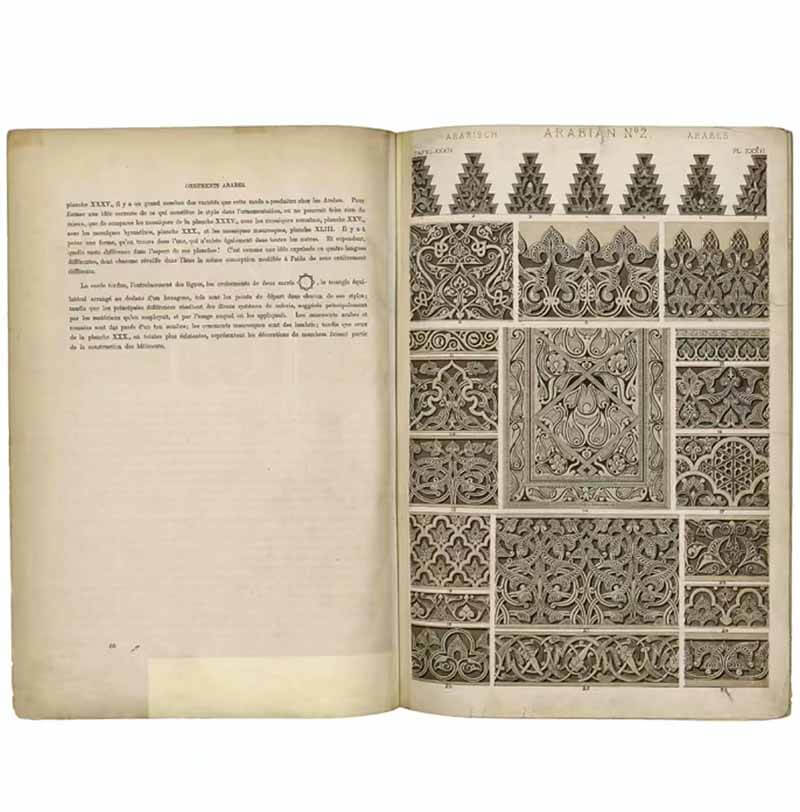

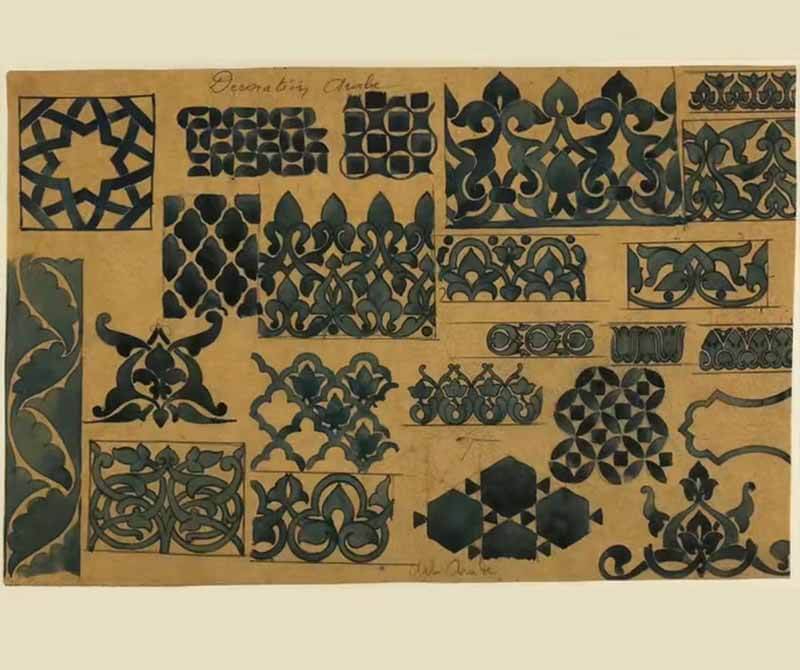

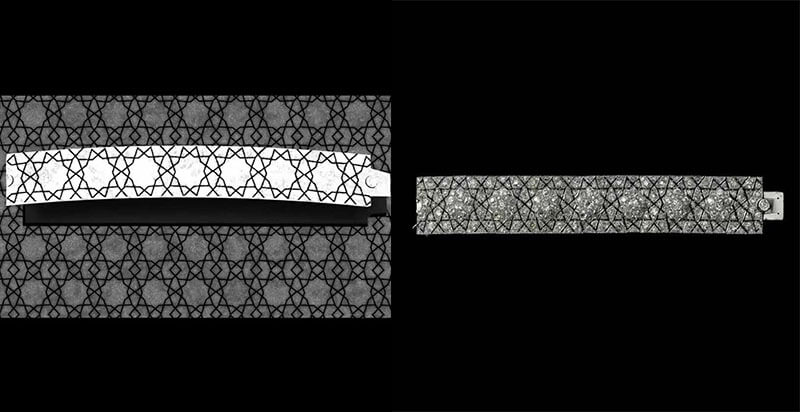

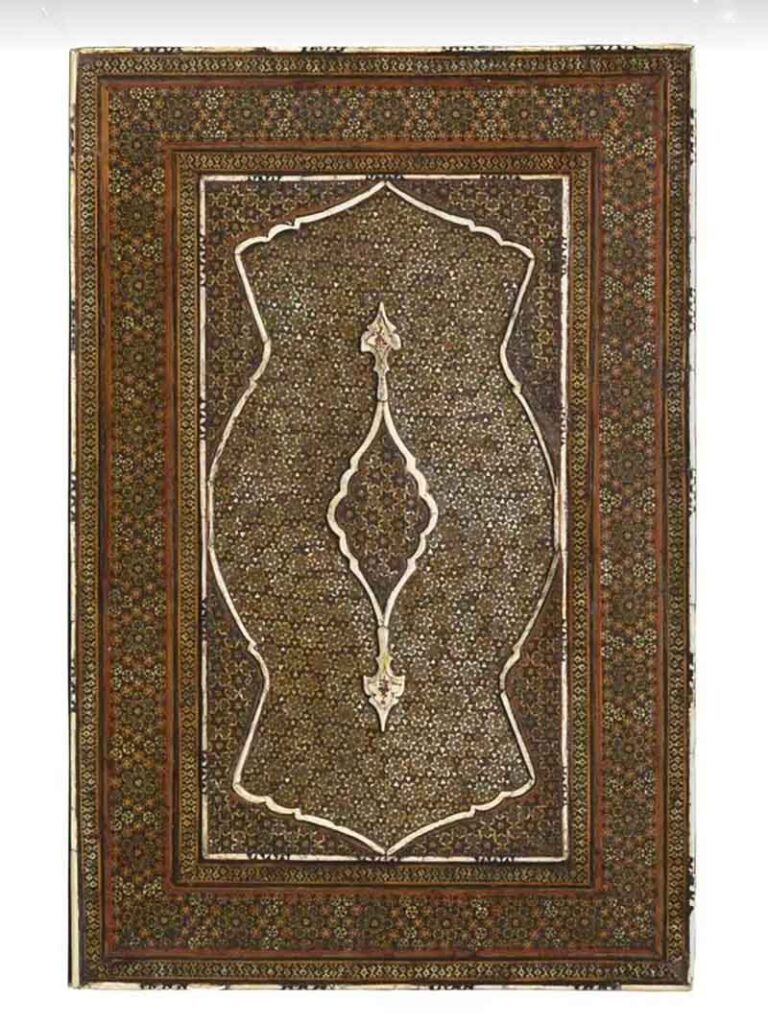

This is Owen Jones’s 1865 book The Laws of Decoration. It is a manuscript of Persian motifs studied in Indian ink by Cartier’s designers. These designers sought to discover how to translate these exquisite patterns into jewelry.

The inspiration of Islamic motifs:

It was a bold experiment. The centerpiece of the box was an ancient Persian miniaturized painting. Cartier creatively sets its jewelry into lapis lazuli, combining antiquities originating from an ancient civilization within its own latest designs.

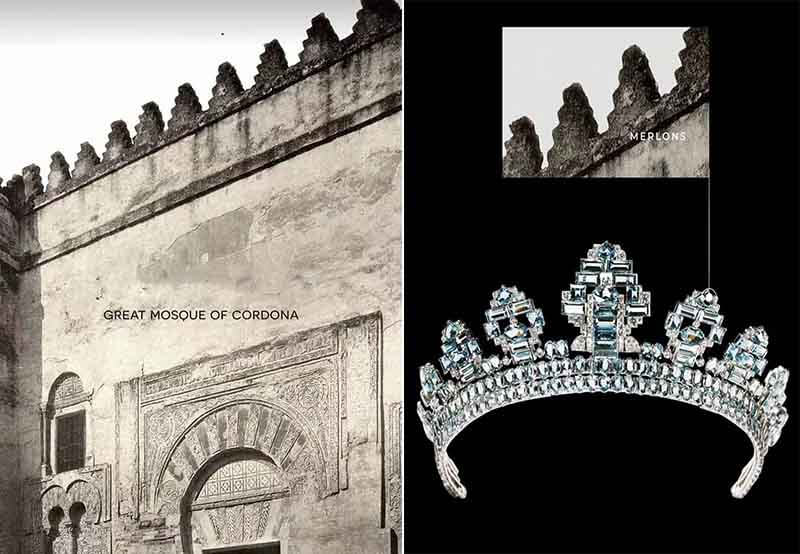

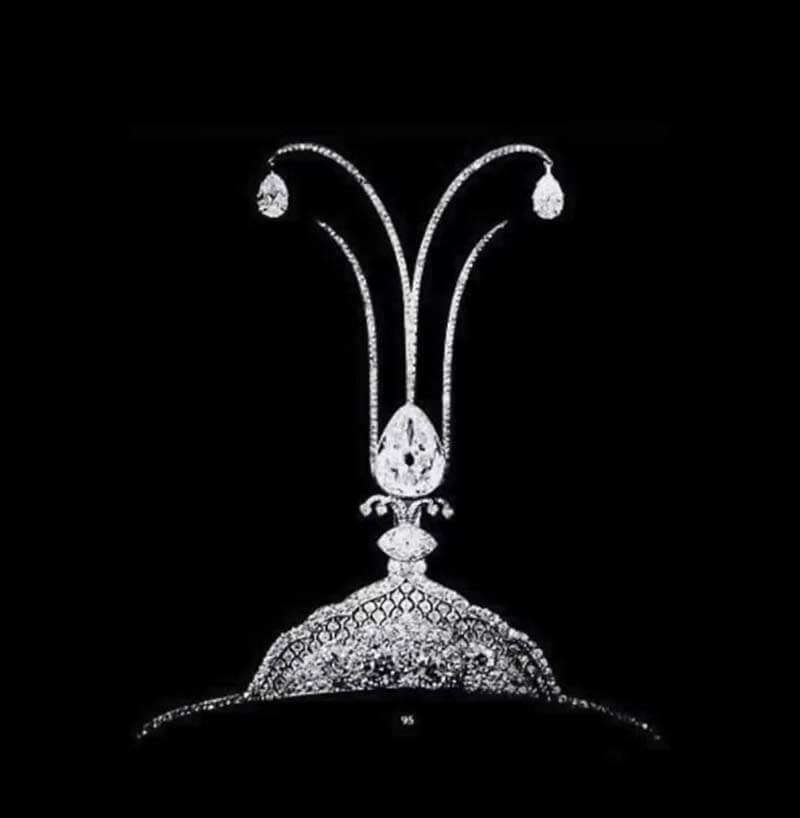

This method of creation was also frequently used in later Egyptian revivals. The motifs of the palace façade of the Mussatta Fortress in Jordan were transformed into this East Asian-style crown.

In 1937, Cartier made this aquamarine cap crown with similar elements in memory of the Great Mosque of Cordoba.

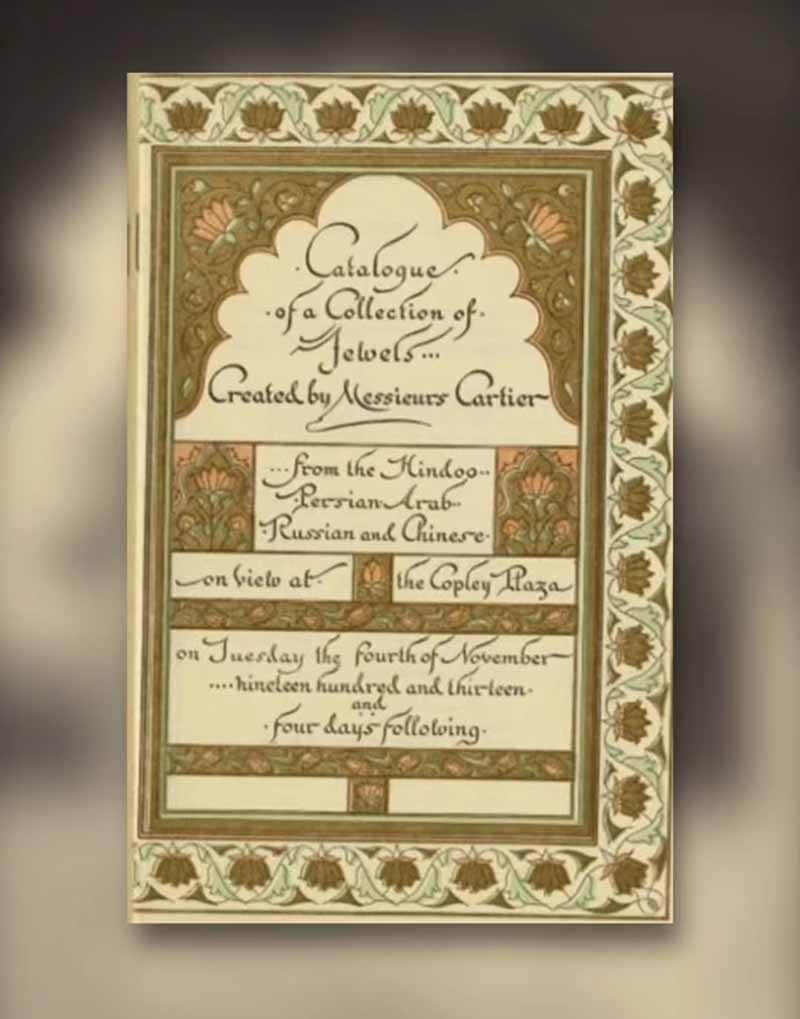

In 1913 Jacques Cartier traveled to India, bringing back a large number of precious stones as well as jewelry made in the traditional Indian craftsmanship.

Cartier’s distinctive style

Upon his return to France, he invited his guests to admire his jewelry. The invitations made by applying elements such as arches were original and unique, yet closely related to the theme.

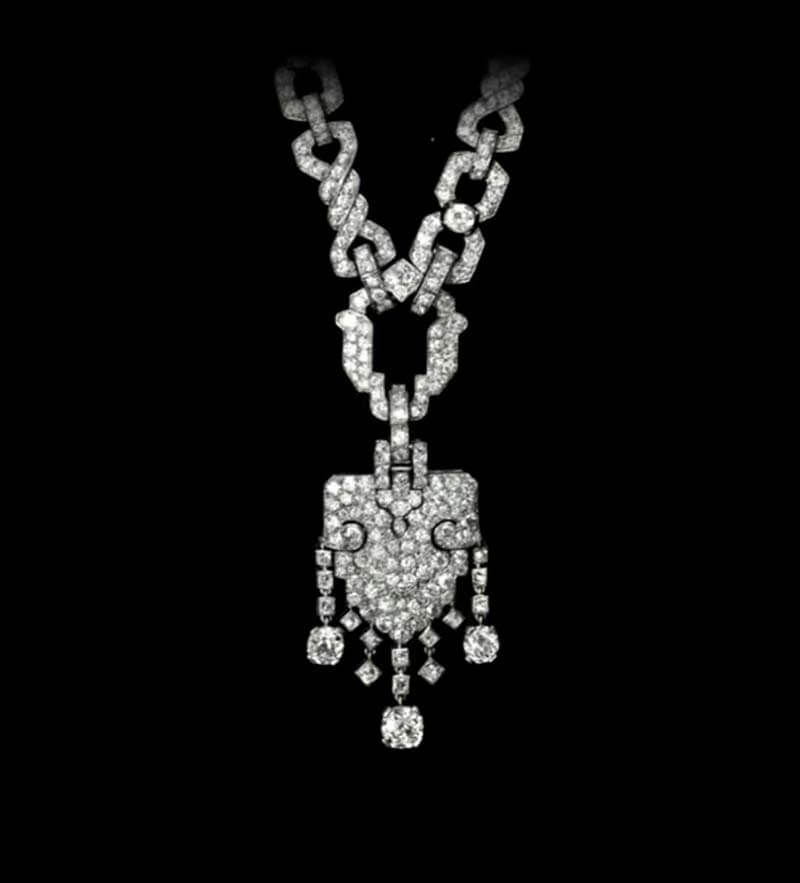

There were even bracelets and headpieces inspired by mosque brick arrangement.

The most memorable is this hairband with diamond picks onyx pavements and red coral inspired by the arched doors and windows of the Islamic school in Qaraouan, Egypt, a raised almond shape known as Mandorla.

Cartier crafted a piece of blackened steel set with teardrop-shaped diamonds, made of a top of the tiara with a rustic flavor.

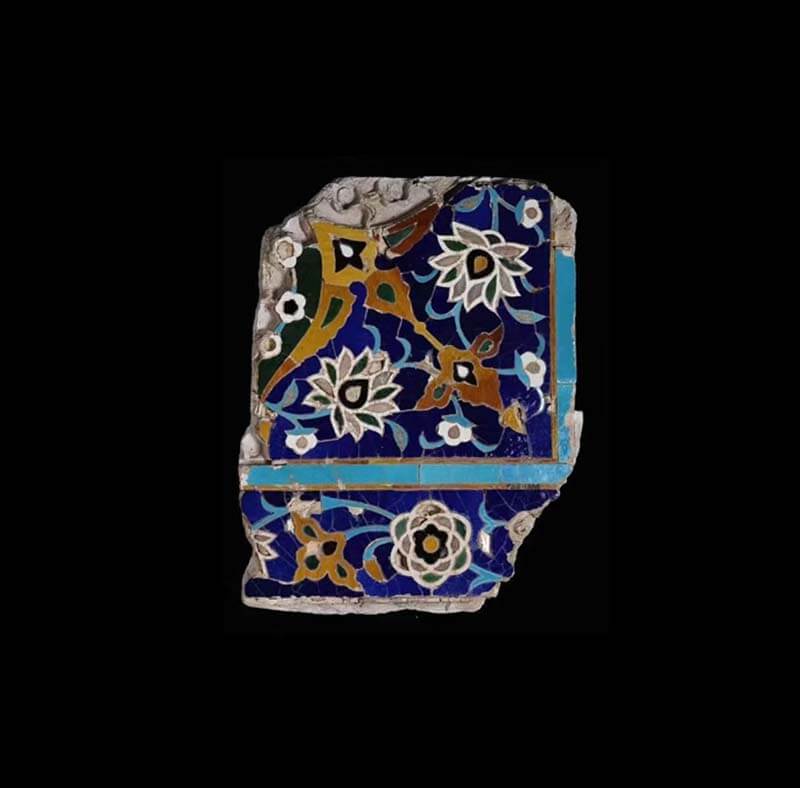

The shawl-like costume accessory, which originally came to Persia from China during the Han dynasty and was used by Islamic craftsmen to decorate ceramic rims, was eventually taken up by Cartier and creatively applied to jewelry.

Inspired by the Persian turban accessory, this hairband is exceptionally airy with its Egyptian egret feathers.

The ruby bib necklace, which Cartier created for Elizabeth Taylor in 1953, is also borrowed from traditional Indian jewelry, which was originally worn by Indian male princes, and is large and luxurious.

Persian-style colorful porcelain plates and a Cartier box with a Persian cypress motif.

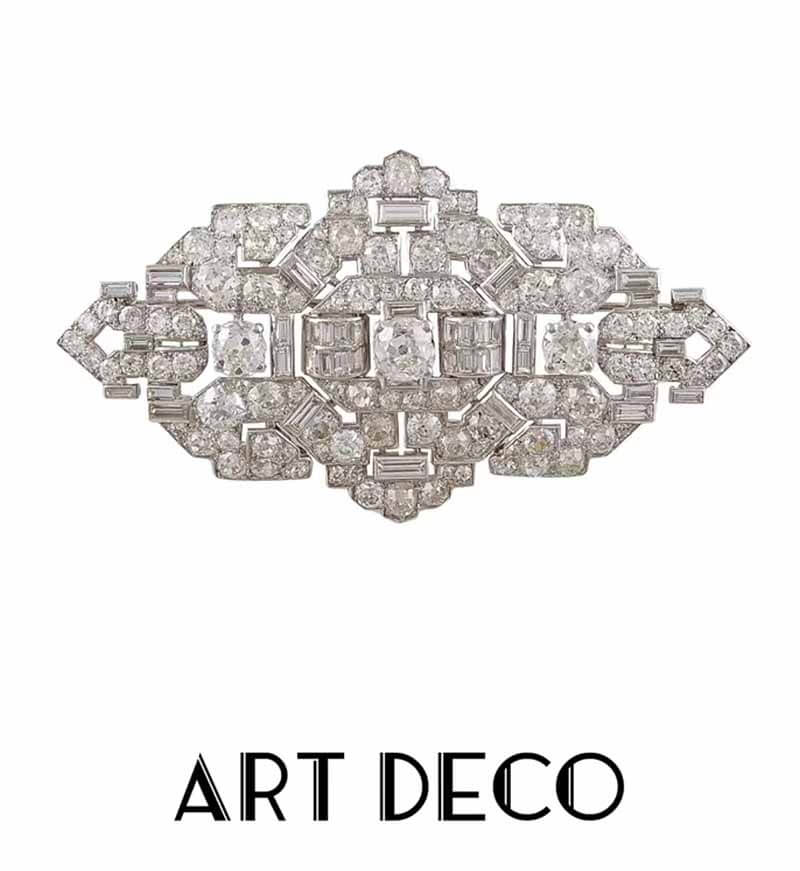

Geometric shapes and lines:

This trend-setting aesthetician eschewed elaborate Belle Époque trim in favor of abstract geometric shapes.

The use of clean lines and geometric motifs created a distinct aesthetic for modern style known as “Art-Deco”.

During this period, Cartier developed several concurrent styles, one of which was a hybrid like this one, combining geometric shapes with flowers and bows in a wreath style.

Another was a more traditional Islamic style, with polygons such as hexagons, octagons and dodecagons in the jewelry.

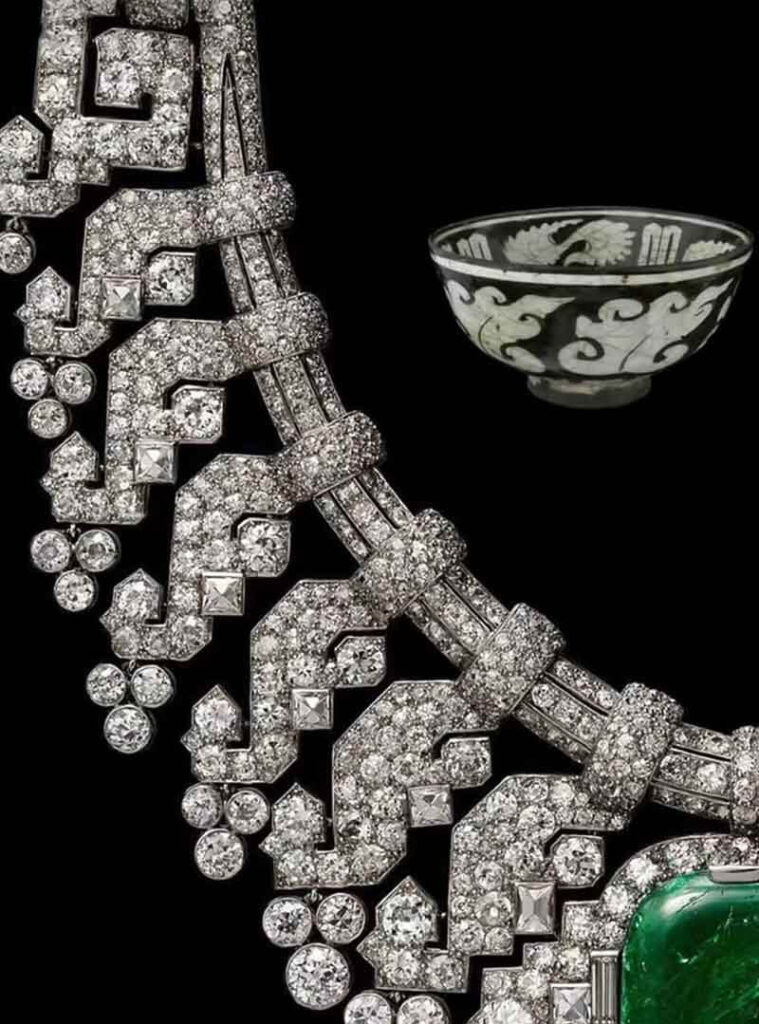

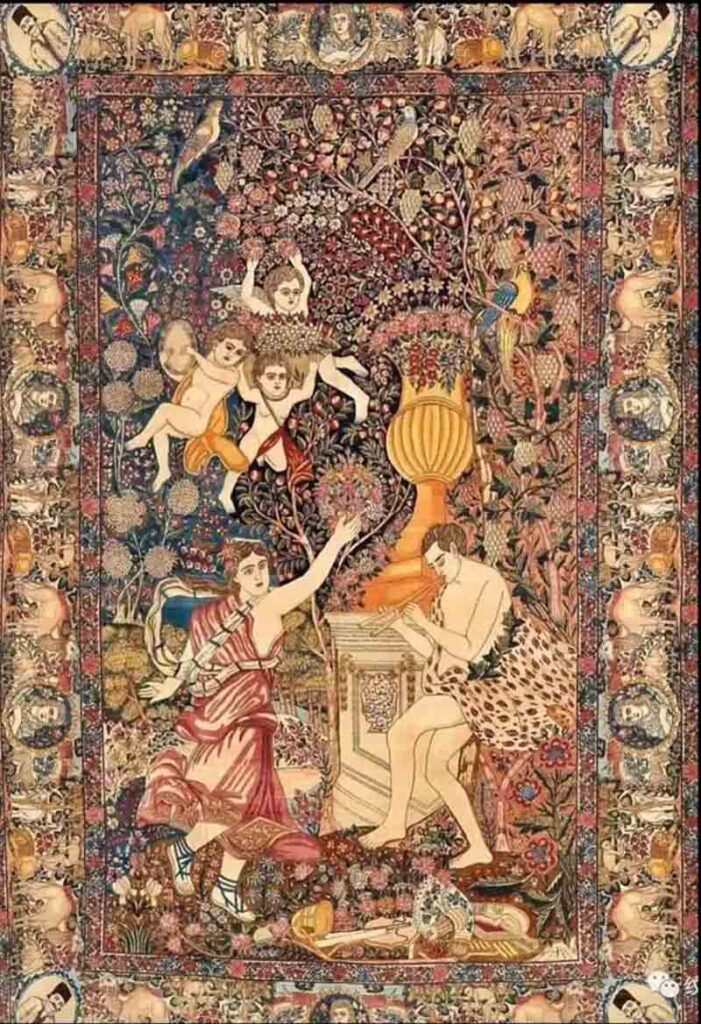

There is also this triangular and circular pattern, often seen on Persian carpets. In this pattern, a large medallion sits in the center, with symmetrical smaller motifs on either side or around it. Cartier, on the other hand, places a large stone or crystal in the center, finishing it off with symmetrical patterns on the left and right.

In this large set, in addition to the eye-catching large emeralds, the S-shaped motif comes from a 15th-century Iranian teacup.

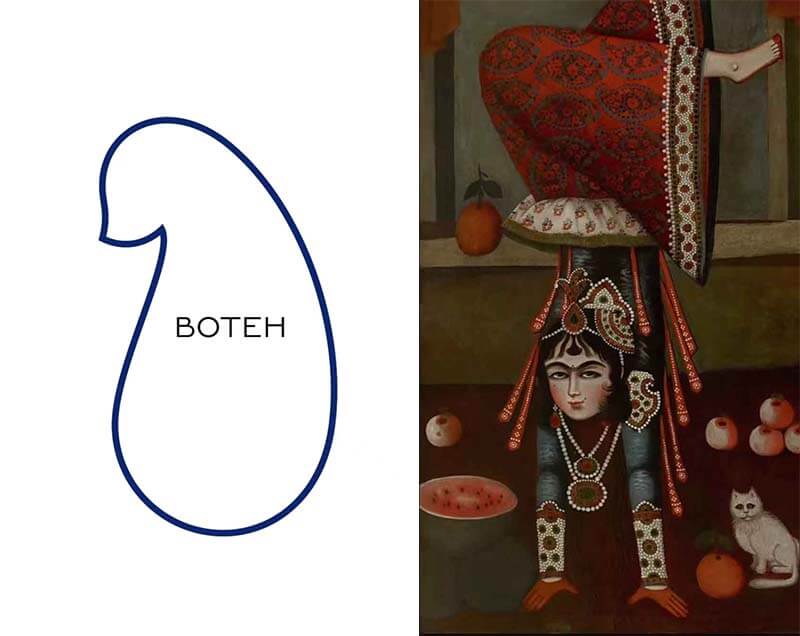

This hooked pinecone motif, known as “Boteh”, was often used to adorn royal costumes during the Qajar dynasty, symbolizing life and eternity.

This lapel pin made by Cartier in 1925 also features a chic pinwheel at the tip.

The interlocking geometric shapes still look timeless today, as well as the scroll and palm leaf-shaped box.

Indian colors:

Leon Bakst designed a blue-green stage backdrop for the Ballets Russes. Blue and green together were once considered taboo by Europeans. However, as the play is widely discussed, this color is subtly changing Parisians’ aesthetics.

Innovative and daring combinations of colors and materials, combining lapis lazuli and turquoise, pairing the green of emerald or emerald with the blue of lapis lazuli or sapphire.

Today this combination has become a signature of the brand and is known as the peacock motif.

This bata-shaped turquoise was carved by artisans into leaves, large in the center and small on the sides, for an elegant and vibrant look.

This emerald, engraved with an inscription, has a special name: “Taj Mahal”.

In 1925 Cartier had it fashioned into a shoulder strap and exhibited it at the Paris Fair.

It was never sold because it was set with two other huge emeralds at the same time, which was expensive.

In 2019, Pansy Ho auctioned it off at Christie’s for more than $12 million. The emerald, which was eventually made into a crown by Cartier, is still on display at the Palace of Hong Kong now.

In addition to sapphire and emerald, Cartier added ruby, which became influential Tutti Frutti jewelry. This was an example of the Art Deco style, a style that continues to innovate today.

Islamic influence on jewelry elements

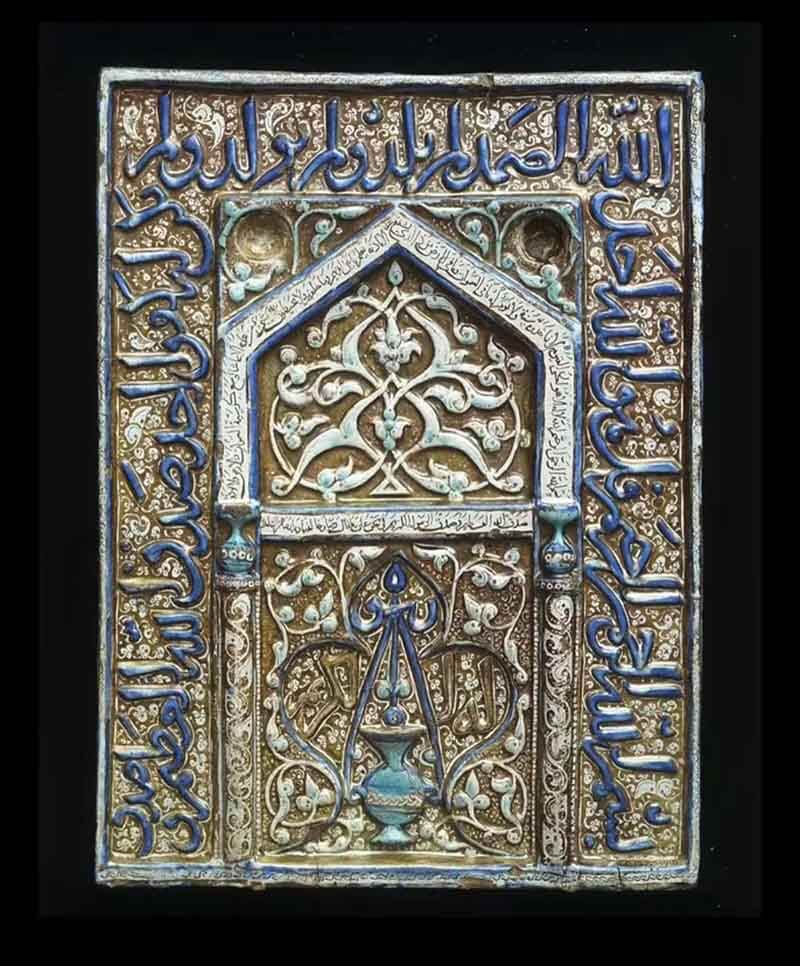

Since Muhammad founded Islam, artists in the Islamic world have adhered to the tradition that Allah does not make images. They have devoted themselves to the construction of shapes and lines. The logic and geometry of Aristotle and Euclid, the precursors of the West, took root where East meets West.

The Alhambra in Spain and the ancient city of Samarkand in Central Asia have left a precious legacy for human. Sensitive jewelry artists have drawn from this legacy to create pieces that, despite the passage of centuries, are still in keeping with today’s aesthetics. These pieces are as bright and vibrant as ever.